|

|

|

|

Stratasys’Bruce Bradshaw.

|

ClearVision’s David Friedfeld. |

|

|

Stratasys was founded in 1988 by Scott Crump, the inventor of FDM (Fused Deposition Modeling, one type of 3D printing technology.) A few years ago, when his patents ran out, other companies jumped into the space, Maker Bot being one of them. The irony being that Crump purchased his own technology back in August when Stratasys purchased Maker Bot for $403 million. Maker Bot, the manufacturer of the type of 3D printer ClearVision currently has in-house, focuses on the hobbyist with a rising interest in the enterprise space, i.e. printers that end up on the desks of designers. “They are used for the modern day version of a ‘napkin sketch,’ the first or second iterations of a design before they are refined for final manufacturing,” said Bradshaw. Last year, Stratasys also merged with Objet, which had developed a different type of 3D technology called Polyjet. Together they are the largest 3D printer manufacturer in the world and comprise 55 percent of the professional 3D printer market. In the professional space, 3D printing is usually used for rapid prototyping but some companies (like Boeing) use it for direct digital manufacturing of end use products.

“3D has been around a long time, it’s not something that is new to industry,” clarified Friedfeld. “Large, multibillion dollar businesses have been involved in this for years but typical small, mid-sized business is not prototyping in this way. I’ve been following it for about 10 years. Within the last two years there has been a big push by the 3D manufacturing companies to simplify the process and bring machines down to a level that was affordable for almost anybody. Once we saw that they were technically easier and more economically reasonable it became a conversation inside the company. Right now we look at this as a way to ultimately shorten the production cycle by being able to be quicker to prototype, that’s an immediate benefit to the company.

“Our objective currently is to just get used to it, be in the game and understand 3D printing so that whether it’s six months from now or a year from now we can take it to the next level. We’re actually getting in what we think is very early in the development of the industry,” he added.

In February, President Obama called out 3D printing as something that could fuel new high-tech jobs in U.S. in his State of the Union address. Obama spoke about the National Additive Manufacturing Innovation Institute, a public-private partnership established in Ohio in 2012 to research how 3D printing technology can be moved from the research phase to day-to-day use. The President announced plans for three more manufacturing hubs where businesses will partner with the departments of Defense and Energy “to turn regions left behind by globalization into global centers of high-tech jobs.” He also asked Congress to help create a network of 15 of these hubs to “guarantee that the next revolution in manufacturing is made in America.”

Friedfeld said, “We do think that potentially, down the line, manufacturing our own frames using 3D printing can be done right here on Long Island but our purpose generally is more on the prototyping, quick to market, reducing time, reducing cost. Being able to remake something very, very quickly, being able to make collections and build a collection to present to licensors or to buyers. That’s how we see it in the very short term,” he explained. “Longer term, we can see it to make more sophisticated items, personalized items and in the very long term, potential for sales to opticians, optometrists dispensers and even longest term, production of short runs.”

“3D printing is impacting personalization,” added Bradshaw. “It is now possible to print one-offs and where it is not time or cost effective to print say 1,000, it is easy to print a tool or a mold for a short run of, say, 500.”

Friedfeld agreed, “What I can see down the road is short run productions that would allow a ClearVision and the consumer to benefit from something that could be done in the U.S., not overseas, and be very close to market and be relatively cost reasonable. As opposed to a short run that might be much more expensive to do and longer to produce in a traditional way through manufacturing in an optical factory.”

|

|

|

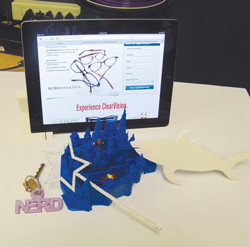

ClearVision’s Maker Bot machine has made an array of 3D printed objects.

|

“We are leaders in the 3D industry and if you pick any industry, be it dental, consumer electronics or optical, 3D printing is changing the way manufacturing is done,” stated Bradshaw. “3D printing is going to bring manufacturing back to the U.S. When you can show the value of something like that to companies like ClearVision, it’s an easy ROI.”

It’s a reality that isn’t that far off. In the early days of 3D printing, the technology was very rough and items required a lot of post finishing. Today, printers can print 17 different materials in different ratios to achieve different affects. The technology exists to print aesthetically clear lenses, a tinted frame and moving hinges all at the same time, according to Bradshaw. Optical quality clear lenses are probably about 10 years off, Bradshaw estimates.

“The part that is interesting and exciting for us is what used to be a two to four month process if you prototyped in the traditional manner, now that can be done literally in one or two days,” said Friedfeld. “It takes about a half an hour to make a front. Once it gets built we can size it on someone’s face, see how the bridge fits, how the eye is centered. All of that in a half an hour and if it doesn’t work then we can just remake it.”

Vision Expo West attendees will have the opportunity to see 3D frame printing in action. ClearVision is bringing its Maker Bot printer to the convention and Stratasys’ Bradshaw, along with Friedfeld, will be in ClearVision’s Booth (#16087) all day on Thursday, Oct. 3 during Expo to discuss 3D printing. ■

dcarroll@jobson.com